This article was first published in Culturewatch.org in two parts, where you can also find my discussion guide. © Tony Watkins, 2012.

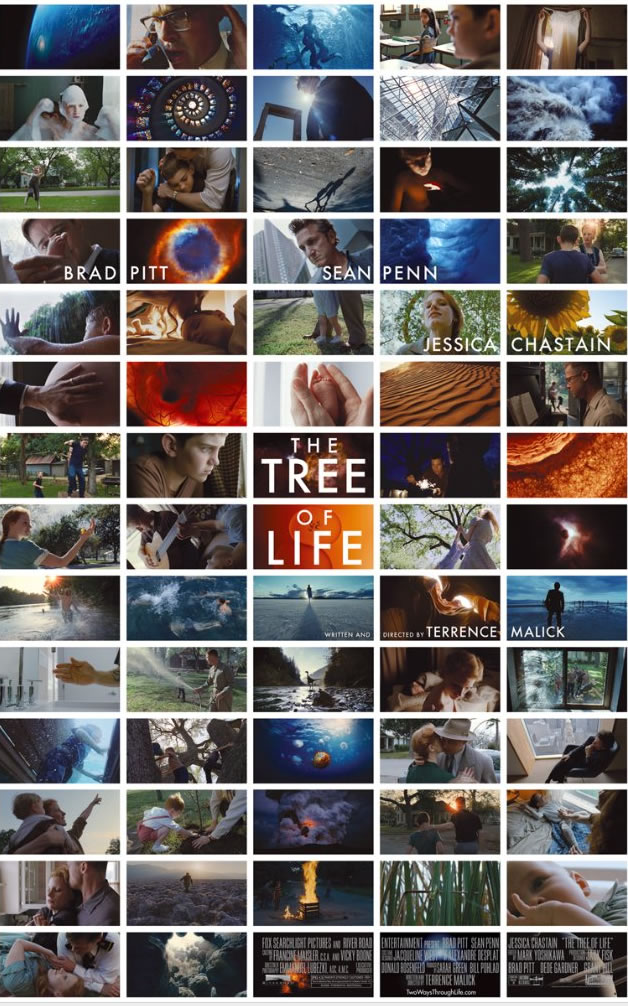

How can we ever understand God? Because he is infinite and transcendent, and we are finite and limited, we often end up thinking about him in very human terms. Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud claimed (without justification) that our idea of God is modelled on our fathers. If Jack O’Brien (played as a boy by Hunter McCracken), the central character of Terrence Malick’s beautiful and elegiac The Tree of Life, did this, what would he think God is like? Jack’s father (Brad Pitt) is very conservative, which is no surprise in 1950s' Texas. He expects Jack and his two brothers, R.L. (Laramie Eppler) and Steve (Tye Sheridan), to treat him with respect, demanding that Jack addresses him as ‘sir’ or ‘Father’, never ‘Dad’. He sees it as their duty to love him.

How can we ever understand God? Because he is infinite and transcendent, and we are finite and limited, we often end up thinking about him in very human terms. Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud claimed (without justification) that our idea of God is modelled on our fathers. If Jack O’Brien (played as a boy by Hunter McCracken), the central character of Terrence Malick’s beautiful and elegiac The Tree of Life, did this, what would he think God is like? Jack’s father (Brad Pitt) is very conservative, which is no surprise in 1950s' Texas. He expects Jack and his two brothers, R.L. (Laramie Eppler) and Steve (Tye Sheridan), to treat him with respect, demanding that Jack addresses him as ‘sir’ or ‘Father’, never ‘Dad’. He sees it as their duty to love him.

He expects the boys to obey him without question, and to carry out his orders perfectly, yet Jack constantly falls short of his father’s standards, and feels his wrath as a result. After one failure, Mr. O’Brien tells Jack that, ‘Toscanini once recorded a piece sixty five times. You know what he said when he finished? “It could be better.” Think about it.’ He is aloof, impatient, and his anger flares quickly. He teaches them to be tough, to fight, and not to be walked over. ‘Your mother's naive,’ he tells Jack. ‘It takes fierce will to get ahead in this world. If you're good, people take advantage of you.’ Yet at the same time Mr. O’Brien genuinely loves his boys, and they share moments of warmth and fun. This inconsistency, and the way he sets rules for others while not keeping them himself, confuses Jack and breeds resentment. Does Jack see God in the same way? It’s hard to be sure, though his bedtime prayer – that God would stop him ‘sassing’ his father or getting dogs into fights – suggests that he sees God mainly as an authority figure.

Malick clearly hints at some connection between young Jack’s attitudes towards his father and towards God. A summer afternoon’s playing in the river turns to disaster when a boy drowns. The lifeguards pull him out quickly and Mr O’Brien attempts to resuscitate him, but without success. The father’s failure to save the boy echoes what Jack sees as God’s failure. ‘Where were you?’ Jack whispers in a voiceover. ‘You let a boy die. You’ll let anything happen. Why should I be good if you aren’t?’ These last words are spoken over a scene in which a fumigation truck travels down the road, puffing thick clouds of insecticide into the air. Jack and other boys run into the smoke shouting ‘I can’t see!’ He feels more confused than ever. Jack’s whispers continue a few minutes later: ‘Why does he hurt us? Our father.’ The images on screen are of Mr O’Brien, but Jack’s words have an obvious double meaning. The incident marks a turning point in Jack’s life. While he has so far resented his father’s rigid discipline, now he begins to defy it.

Terrence Malick is known for the poetic, reflective nature of his films, and he handles narrative in unconventional ways. Often he interrupts the flow of the story with images and short scenes which don’t obviously fit. Sometimes this serves to create an impression of various aspects of life for the characters (perhaps influenced by the German philosopher Martin Heidegger, who was the subject of Malick’s postgraduate research)1, but sometimes they seem unconnected, even surreal. However, this apparent randomness is an illusion; they mean something important to Malick. They often connect with other moments or images in the film, and they are tied to the scenes around them by the music – an aspect of film which is profoundly important to Malick. The meaning may not be obvious at first viewing, but gradually the subtle interplay of ideas and emotions becomes clearer.

Soon after the drowning incident comes a fight over the dinner table: Jack seems to have stolen something and his father is cross. R.L. tells their father to be quiet, provoking him to rage. As we watch Mrs O’Brien (Jessica Chastain) upset by her husband’s anger, we hear John Taverner’s ‘Funeral Canticle’ (returning from when we first see the family at the beginning of the film). Something has died or is dying – in the family or in Jack’s heart. While this music continues, we see Jack dancing on the house steps, surprisingly carefree (an indicator of him rejecting his father’s discipline?), then trying to read and to peer around his bedroom by the narrow beam of a torch. The music now changes, serving to connect this scene of restricted vision with what at first appears to be one of the most out-of-place scenes: a clown at a fun fair. After a moment, we see behind the clown a banner with the word ‘creation’ in large letters. The clown plays a trick on someone and then we see him plunge into a deep tank of water and cry out under the surface. As Jack looks on, the link with the boy’s drowning is clear. In Jack’s mind, the creation is a joke and God is a clown, a trickster who deserves to drown.

Jack’s questions about why God let the boy die resonate strongly because it is not the first death in the film. Within the first five minutes, we see Mr and Mrs O’Brien receive news of the death of one of their sons. As the film unfolds, we realise that it is R.L. who dies a decade or so after the main sequences of the O’Brien family. Over images of grief and of the funeral, we hear the mother’s voiceover, expressing her sense of desolation, just as we hear Jack’s later on. The minister of the church tells her, ‘He’s in God’s hands now,’ and we hear her whisper, ‘He was in God’s hands the whole time. Wasn’t he?’

However, there is a profound difference between the mother’s and Jack’s attitudes as they question God. Jack feels betrayed, angry, and accusing; his mother – though distraught and bewildered – is grounded in a basic attitude of trust in God. ‘My hope,’ she continues. Does she mean the son was her hope, which is now dashed, or is she addressing God as her hope in the midst of grief? The tone in which she then says, ‘My God,’ suggests the latter. She feels lost and helpless, but God remains the one firm rock. She continues, reflecting on Psalm 23: ‘I shall fear no evil – fear no evil, for you are with me’ (Psalm 23:4, ESV), but she can still ask, ‘What did you gain?’ She quotes Psalm 22: ‘Be not far from me, for trouble is near’ (v.11, ESV). The music playing during this sequence is ‘Morning Prayers’, by Georgian composer Giya Kancheli, suggesting an attitude of submission to God at the beginning of this new and difficult time. There is no contradiction here. The Bible has many examples of people in difficult circumstances crying out to God, expressing dismay or even anger at what God has allowed to happen, yet within a framework of faith in God and his goodness. This includes Psalm 22, which Jesus quoted from when dying on a Roman cross.2

Mrs O’Brien’s mother tells her that she must be strong now: the pain will pass, life goes on. ‘The Lord gives and the Lord takes away,’ she says, ‘and that’s the way he is. He sends flies to wounds that he may heal.’ The phrase about the Lord giving and taking away is drawn from the Old Testament book of Job. When Job learns that his large flocks and herds have been stolen, and that all his children have been killed, he says, ‘The Lord gave and the Lord has taken away; may the name of the Lord be praised’ (Job 1:21, NIV). Job is not piously denying his grief, but recognising a bigger perspective: what God does may not be something we finite humans can understand, but he remains fundamentally wise, loving and right, and he can be trusted even in the darkest times. That doesn’t mean that we should not ask questions, but it frames the way we ask them.

The next 36 chapters of the book are about Job and his unhelpful friends trying to answer the question of why such bad things have happened to him. Job’s ‘comforters’ are sure he must have done something wrong in God’s eyes. Jack wonders the same thing after the accident in the river: ‘Was he bad?’ But Job had done nothing; he was ‘blameless – a man of complete integrity. He feared God and stayed away from evil’ (Job 1:1). Like the book of Job, The Tree of Life is about wrestling with the question and, more fundamentally, with the experience of suffering and death (another strong link with Heidegger).

There is a very personal aspect to this for Terrence Malick. He grew up in Waco, Texas, in a family like that in the film, in the same period. Like Jack, he was the oldest of three boys, with a father who worked in the petroleum industry. One of his brothers, Larry, went to Spain in the late 1960s to study guitar under the great, but demanding, Segovia. In his book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Peter Biskind recounts that the pressure on Larry drove him to break his own hands. Their father asked Terrence to go to see Larry, as he was then a Rhodes Scholar, studying postgraduate philosophy in Oxford. ‘Terry refused,’ writes Biskind. ‘The father went himself, and returned with Larry’s body. He had apparently committed suicide. Terry . . . always bore a heavy burden of guilt.’3

God never explains to Job why he experienced such terrible suffering, but he answers him with a challenge of his own (Job 38 – 41): ‘Who is this that questions my wisdom with such ignorant words? Brace yourself like a man, because I have some questions for you, and you must answer them’ (Job 38:2–3). God’s series of questions to Job are impossible for a man to answer. Terrence Malick quotes from them at the start of The Tree of Life: ‘Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth? . . . when the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?’ (Job 38:4,7, NKJV). This is what is behind the stunning extended creation sequence immediately after the sequence of loss and grief. Were you there when God created everything? Do you understand it, or even get the measure of it? Could you do any of it? Do you have enough wisdom that you know better than God? Or could it be that what God does is so far beyond human comprehension that you are simply too limited to be able to make sense of what he does, even with a single human life?

The pain of loss is still agonising, of course. God may be beyond our comprehension, but he doesn’t ignore our pain; rather he understands it – even feels it – better than we dare to imagine. This, surely, is why Malick chose the agonisingly beautiful ‘Lacrimosa – Day of Tears’, from Zbigniew Preisner’s Requiem For a Friend, to play during the first half of the creation sequence. It is almost as if Malick is seeing the countless stars as the tears of God for all the pain that will eventually come.

This sequence is, it seems, playing out in the mind of Jack as a middle-aged adult (now played by Sean Penn). Many years later, he is struggling again with memories, questions and the pain of loss. Early in the film he wakes from troubled sleep, his wife concerned but powerless to help him, and his working day as an architect is disrupted by his heartache. From a telephone call with his father, we realise that he has said something hurtful, for which he apologises, but it has sent his mind circling and weaving around like the flock of starlings he watches in the sky. Jack realises that he has lost sight of grace and of its giver, God. ‘How did I lose you?’ he asks. ‘Wandered? Forgot you?’ In response, he seems to imagine himself in a dry, rocky desert. He is looking for something: refreshment? Understanding? Peace? As he reflects on the question of how his mother bore the pain, he recalls her grace and faith, and then has this extraordinary vision of creation which opens his mind again to God’s greatness.

It is after this that Jack replays in his mind the events of his childhood, before having a vision of earth’s destruction, and of the new heavens and new earth. The vision of creation has reminded him that his perspective is too limited to understand everything. The memories of his childhood have reminded him of the grace he experienced through his mother and brother. Now the vision of the new creation reminds him that the day will come when all the brokenness of this life will be over, and God will put everything right.

The question of why God acts in certain ways is, finally, a mystery to us. But perhaps we can still understand something of how God acts. Almost at the very beginning of The Tree of Life, Malick establishes the tension that runs throughout the film: nature versus grace. The mother explains in a voiceover:

The nuns taught us there are two ways through life: the way of nature and the way of grace. You have to choose which one you’ll follow. Grace doesn’t try to please itself. Accepts being slighted, forgotten, disliked. Accepts insults and injuries. Nature only wants to please itself. Get others to please it too. Likes to lord it over them. To have its own way. It finds reasons to be unhappy when all the world is shining around it. And love is smiling through all things. The nuns taught us that no one who loves the way of grace ever comes to a bad end. I will be true to you. Whatever comes.

It is clear that the mother has embraced the way of grace, while the father embodies the way of nature. The mother brims with warmth and joy and love, while the father is often cold, stern and demanding. ‘Mother. Father,’ whispers Jack late in the film, ‘Always you wrestle inside me. Always you will.’ At one point he sneers at his mother, ‘You let him run all over you.’ The viewer already knows why: ‘Grace . . . Accepts being slighted, forgotten, disliked. Accepts insults and injuries.’ Jack rejects what he perceives to be his mother’s weakness, and follows his father down nature’s path – especially after his school friend drowns.

Soon Jack is causing trouble with his friends, letting his curiosity get the better of him, and blindly following his urges and instincts. He becomes cruel to R.L., daring and goading his younger brother to trust him, and then betraying that trust. After tipping water over R.L.’s painting, he defies his mother, insisting, ‘I’m not gonna do everything you tell me to. I’m gonna do what I want.’ R.L.’s spoiled creation is an obvious metaphor for the bigger picture that Malick is painting: the way of ‘nature’ leads eventually to ruin. But deep inside, Jack is weighed down by guilt and shame. ‘What have I started?’ he asks in a voiceover. ‘What have I done?’ He senses that he is stuck on this path and asks, ‘How do I get back – where they are?’ – a recognition that his brothers and his mother are on a different path.

The answer to Jack’s problem comes in the overlap of three very short scenes. In the first, he walks down a railway track after another outburst (a clear metaphor for his inability to choose an alternative path), and we begin to hear the dialogue from the next scene – the voice of the minister at a confirmation service: ‘Defend, O Lord, this thy child with thy heavenly grace, that he may continue thine forever . . .’ What Jack needs is God’s grace. The way of nature is not able to deal with the problem of the human heart. We may be able to live outwardly proper lives, as most people would say Jack’s father does, but inwardly we remain deeply flawed, full of anger, perhaps, or pride or self-seeking. Jack laments, ‘What I want to do, I can't do. I do what I hate’ (a paraphrase of Romans 7:14–24). We do not have it within us to save ourselves. Malick knows that Jack – and each one of us – needs a divine rescuer. We need God’s grace – his goodness to those who don’t deserve it. As the scene changes to the confirmation service, the minister’s words continue: ‘. . . and daily increase in thy Holy Spirit more and more.’ But, surprisingly, we see it’s R.L. who is being prayed for. Jack needs ‘heavenly grace’, but R.L. already seems to be marked by it, like his mother. What he needs is to grow in grace as God’s Holy Spirit works in him. Jack is next in line to be prayed for, but he is looking the other way. The minister’s words continue over the next shot, evoking hope as we see Jack alone, walking slowly down the street as evening falls: ‘. . . until he come unto thy everlasting kingdom.’

The watershed for Jack comes when he shoots the end of R.L.’s finger with his air gun. Jack is remorseful and offers R.L. the chance to whack him with a large piece of wood. But his brother declines, and instead offers him forgiveness. It’s a remarkable gesture, since Jack has done nothing to deserve it. But that is the very essence of grace. In this one act of grace, Jack has seen more of the real nature of God than he has ever seen in his father. The Bible is clear that of all the many characteristics of God, one of the most fundamental is his love: God acts in love and in grace.

To underline the significance of the reconciliation, as the boys run out into the garden to play, the camera cranes away from them, up into the boughs of the enormous tree in their garden (a tree which Malick had transported several miles to plant outside the house he was using for filming). This tree is old and beautiful; the boys enjoy climbing it together, and they have a swing hanging from one of its branches. It symbolises stability and ancient roots, and is a place of pleasure and harmony. This tree is not the ‘tree of life’, but it serves to remind us of it. The tree of life was in the garden of Eden, and human beings were free to eat its fruit. There was only one tree that was off limits to them: the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Yet Adam and Eve deliberately defied God by eating the fruit from this tree, and they were shut out of the garden. They could never go back to the tree of life, and ever since, human life has been marred by pain and death. This is the agony at the heart of Malick’s film: life is wonderful, beautiful, and delightful, but it is also full of pain, suffering and death. Perhaps, in using this particular tree as a metaphor for the good times in the O’Brien family’s life together, Malick is suggesting that the original tree of life echoes down through human history, even though we are cut off from it.

At least, we are cut off from the tree of life until the new heavens and new earth when, at the end of the apostle John’s highly symbolic vision in the Book of Revelation, it will be found on either side of a ‘river with the water of life’ (Revelation 22:1). Water, like the tree, is a recurring motif in The Tree of Life, but it is often linked with death rather than life. However, at times, Malick is perhaps using it to hint of the new creation to come, including in the shot immediately following the one just referred to. As the camera rises in the tree, Jack’s voiceover reflects on what has just happened – ‘What was it you showed me?’ – and the scene changes to the river. Now the river is calm and beautiful, evoking life not death, peace not distress. The voiceover continues: ‘I didn’t know how to name you then. But I see it was you. Always you were calling me.’ Now we are able to make sense of the very first voiceover in the film. After the initial slate with the quote from Job, we see an abstract glowing shape, which we eventually realise is associated with – or symbolises – God, and we hear the adult Jack saying, ‘Brother. Mother. It was they who led me to your door.’

Jack had been stuck on the way of nature, with no way to redeem himself, but now grace has begun to transform him. We see the proof of this immediately, as he plays in the street with a boy who had been hurt in a fire, whom he previously disregarded: Jack is reaching out in grace to someone else. Even more surprising is that he then reaches out to his father, too, making the first move to go and help him in the vegetable patch. This is how grace works: those who are able to receive grace become agents of grace in other people’s lives. It can become a chain reaction. This is what seems to happen in some way here, as the film moves from the first steps of reconciliation between son and father, to the father’s humble realisation that he has missed something vital in life: ‘I wanted to be loved because I was great. A big man. I’m nothin’. Look – at the glory around us [as the camera gives us a shot of Mrs O’Brien’s warm smile]. Trees and birds. I lived in shame. I dishonoured it all and didn’t notice the glory. I’m a foolish man.’

The final sequence of The Tree of Life is the most difficult to understand, and the most disliked by critics. We are back with Jack in the present day, imagining himself in the rocky desert, following a woman in a grey flowing dress through a door frame standing isolated in the barren landscape. The woman is not his mother, but she is clearly leading him. Is she an angel, along with the woman in black in the earlier part of Jack’s vision who wraps R.L. in a white gauze curtain like a burial shroud, and the woman who appears to beckon R.L. out of a grave near the end? Or is she – maybe all three mysterious women – even a representation of God?

Jack’s vision switches now to the destruction of the earth in the far future as the sun, now a red giant, consumes it. ‘Keep us,’ prays Jack. ‘Guide us till the end of time.’ Jack has reached the same point as his mother of trusting God even when he doesn’t have answers to all his questions. Young Jack’s voice whispers, ‘Follow me,’ and in the adult Jack’s vision he follows his younger self through the arid terrain, finally reaching a beach at sunset, on which people are walking around. Jack kneels in wonder and worship; the woman in grey comes and touches his head, then stands in front of him, and Jack clasps her feet in a gesture of reverence and devotion. We see some people from Jack’s past: the boy who had been harmed in the fire, his brother Steve, his mother and father, and finally R.L. This is a place of restoration after pain and death; it is a vision of the new creation – the new heavens and new earth of Revelation 21, when the apostle John hears a loud voice from God’s throne saying, ‘Look, God’s home is now among his people! He will live with them, and they will be his people. God himself will be with them. He will wipe every tear from their eyes, and there will be no more death or sorrow or crying or pain. All these things are gone forever’ (Revelation 21:3–4). This vision of the final triumph of grace is accompanied by the ‘Agnus Dei’ from Berlioz’s Requiem, which is a prayer to the ‘Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world’ for eternal peace. The vision fades, and Jack is back in his ultra-modern surroundings. But the distress has gone; Jack is now at peace in his world because he has new confidence in the world to come, a world in which the questions about suffering and death are finally resolved because God will have put things right.

The final shot of the film is of a bridge, a profoundly appropriate image as it is a metaphor of connection or reconciliation, not just between estranged people, but between God and humanity. Where there was a divide between us that we could not cross, God’s Son, Jesus Christ, has made a bridge. He came into our world, to be born as a human being, taking on our nature, yet without being infected by its fallenness. And he died in our place – the one perfect man, who is also God, dying the death that we deserve for choosing to reject him and take the path of nature. Like Mr O’Brien, we live in shame, dishonouring it all because we don’t notice or acknowledge God’s glory. We are foolish people. But we are the people for whom Christ, the Lamb of God, died. That is the ultimate demonstration of grace.